Source: Wild, some farmed

Mercury Risk: Low

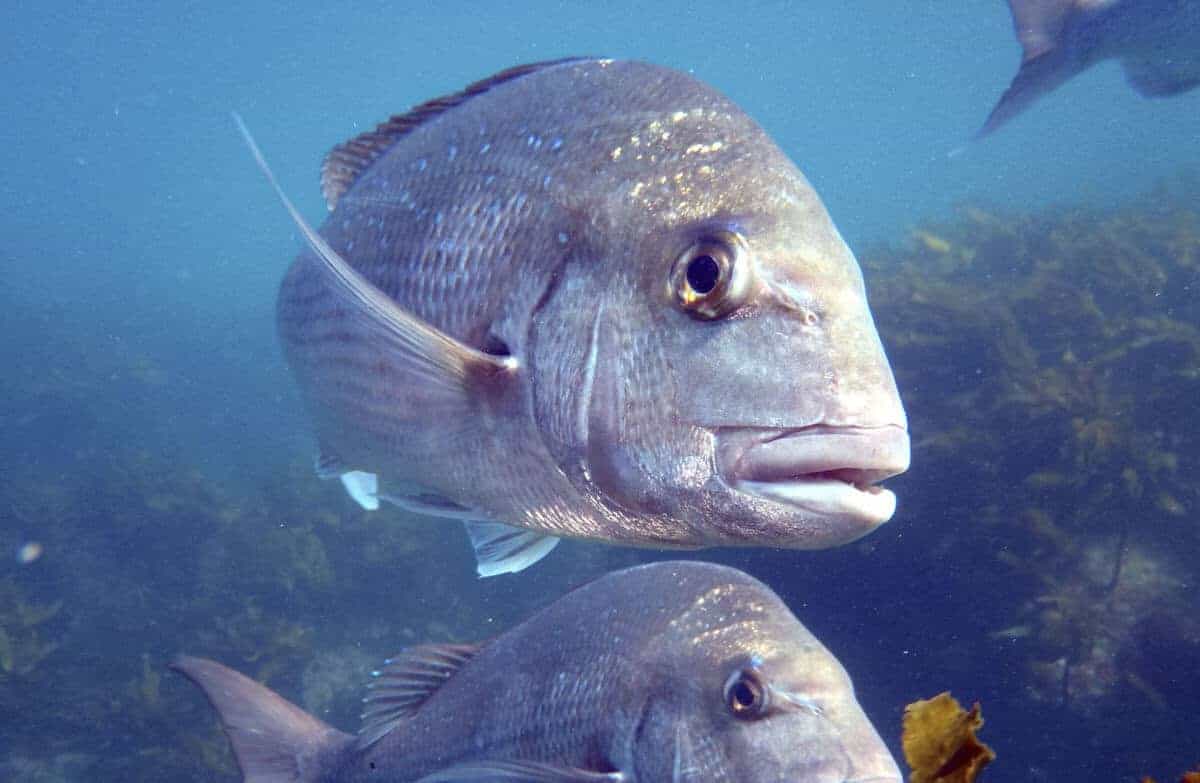

Tai is a fish of many faces. The English equivalent of the word is usually considered to be “snapper,” an equally ambiguous term that means very little. Just about anything can be called a snapper, but usually it refers to some type of a long-living fish that grows slowly and lives in rocky areas. These fish are also tagged with other meaningless monikers like “sea bream” and “sea perch.” None of this makes it any easier to choose sustainable tai.

In Japan the preferred option is generally Pagrus major. This fish is in high demand and is known by a number of English names, most commonly red sea bream and Japanese sea perch. The technical Japanese term for this fish is madai, or “true tai.”

Madai is extremely popular in Japan, and it is traditionally served at celebrations and festive occasions. This cultural significance, coupled with North Americans’ historic indifference to the fish, has forestalled any major exports of the product to the United States. This situation is beginning to change, however. Madai aquaculture is a major industry in Japan, Taiwan, and China, and some of these farms are now selling their product to the Western market. Even so, madai is not yet readily available in North America, so more accessible alternatives are often served in its place.

Sushi bars in the southern United States and along parts of the East Coast often use Pagrus pagrus, the red porgy, as tai. Red porgy is caught along the Atlantic coast of Florida and in the Gulf of Mexico. Historically the Atlantic fishery has been the more productive of the two, but stocks fell sharply during the late twentieth century. It was not until after fish populations had been significantly depleted that any management protocols were put in place.

As red porgy landings declined in the Atlantic fishery, they began to increase in the Gulf of Mexico. Currently the majority of red porgy consumed in the United States is caught in this region. Unfortunately, there have been no stock assessments conducted on Gulf of Mexico red porgy populations, and beyond state waters, there is no management in place.

If the tai at your local sushi restaurant isn’t Japanese sea perch or red porgy, it might be Lutjanus campechanus, the ubiquitous red snapper. This popular fish is also caught primarily in the Gulf of Mexico, and like the red porgy it is potentially in serious trouble. Stocks are known to be overfished, but they are still being exploited at levels beyond what the population can support.

There is also a significant amount of red snapper imported into the United States, mainly from Latin America. Little in known about the status of these stocks, but it is possible that they are facing problems similar to those of domestic red snapper.

Vermillion snapper is also caught in the Gulf of Mexico. Like red snapper, vermillion snapper is overfished, and although there is management in place, populations continue to decline.

Finally, the newest addition to the lineup is Pagrus auratus, often known as New Zealand tai snapper, or kodai. There are several tai snapper fisheries in the waters around New Zealand. Known as tamure among the Maori, the native people of New Zealand, this fish has long been of great importance to New Zealanders, but it has only recently gained a following in the United States. The current situation is somewhat chaotic: A number of the fisheries are overfished and poorly managed, while others boast healthy populations and strong management.

Here’s how tai plays out at the sushi bar:

Farmed madai imported from Asia is potentially a better choice than domestic wild alternatives. That being said, it can be difficult to locate. Moreover, not enough is known about farm management or environmental impacts to justify an unalloyed recommendation.

Wild red porgy from the Atlantic is not a perfect choice, but there is management in place now, and stocks seem to be recovering.

Wild red porgy from the Gulf of Mexico is potentially an unsustainable choice, but not enough is known to say for certain. Still, until more research is done on stock strength and strong management protocols are imposed, this fishery will continue to be a free-for-all.

Red snapper from the Gulf of Mexico is dangerous as well. The stocks are weak and only growing weaker as overzealous fishing pressure continues.

Vermillion snapper from the Gulf of Mexico is also a risky selection. Until populations stop declining and begin to rebuild, it is best to select a more sustainable option.

Other snappers from the Gulf of Mexico are more difficult to assess. Some chefs may use yellowtail, gray, lane, or mutton snappers as tai. Yellowtail snapper populations look healthy, but there isn’t enough information available to be sure. Even less is known about the other snapper populations, so order these species with some caution.

Red snapper imported from Latin America poses a difficult problem. Not enough is known about it to justify a red ranking. However, many believe that Latin American stocks may be suffering like those in the Gulf of Mexico. It’s best to be cautious.

New Zealand tai snapper is not perfect, but management does exist, and the stock status is fairly well understood. This is potentially a better choice then most of the other common options. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of enjoying tai is the general lack of knowledge as to what species is actually being served. As a general rule, consider bypassing tai for other options—U.S. farmed striped bass and barramundi are both excellent alternatives.

Casson Trenor

Casson Trenor is a frequent commentator on sustainable seafood issues. He has been featured in regional, national, and international media outlets, including CNN, NPR, Forbes, New York Times, Boston Globe, Christian Science Monitor, San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Times, Seattle Times.